In this article, we discuss DNS lookups — what they are, how they work, and how they impact online privacy and censorship.

A DNS lookup refers to the process of matching the URL you enter into your browser’s address bar (the readable domain name) to its corresponding IP address.

All devices that connect directly to the internet are identified by a numerical label known as an IP address. To help make things easier for us humans, this address can also be identified using more readable and memorable domain names. The Domain Name System (DNS) maps these domain names to their corresponding IP addresses.

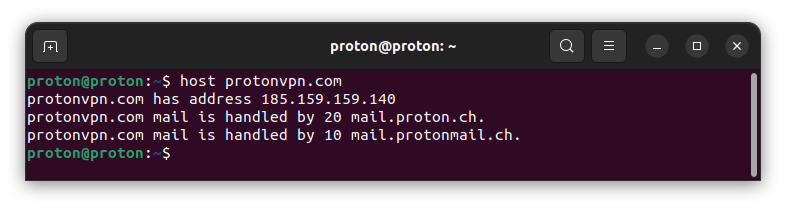

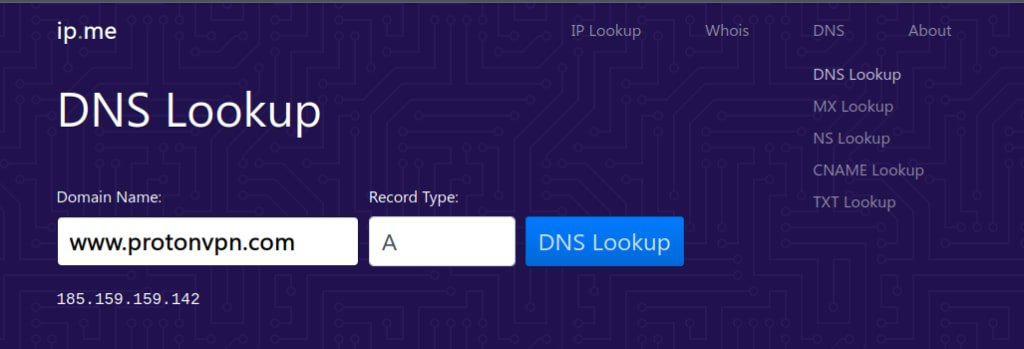

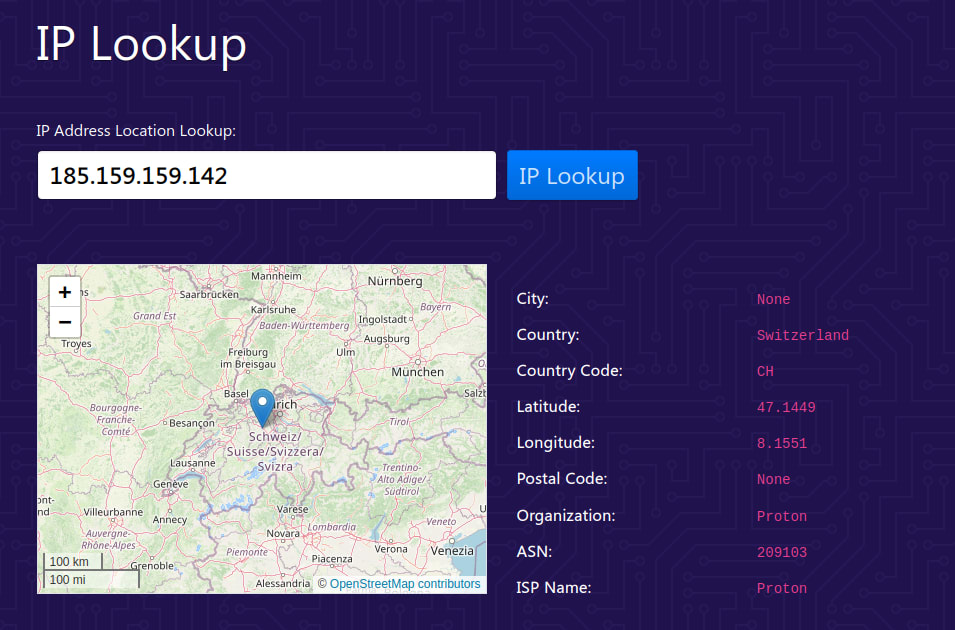

For example, the Proton VPN website uses the domain name protonvpn.com, which corresponds to the IP address 185.159.159.140. When you type www.protonvpn.com into your browser’s URL bar, the domain name must be converted into its corresponding IP address for computers to understand it.

This conversion is performed using DNS. So when you type in protonvpn.com, DNS converts the domain name into the IP address: 185.159.159.140. This allows your browser to locate and connect to the correct website.

Domain names exist solely for human convenience and aren’t required for the internet to function. If you could remember IP addresses, you could type those in directly. To see this in action, simply enter 185.159.159.140 into your browser’s URL bar, and it will take you to the Proton VPN website.

- How a DNS lookup works

- DNS, censorship, and government surveillance

- Third-party DNS services

- DNS and VPNs

- NetShield Ad-blocker

- DNS leaks

- Common DNS record types

- DNS lookup commands

- DNS lookup tools

How a DNS lookup works

DNS is often compared to a telephone directory that cross-references domain names and their corresponding IP addresses. This is a useful analogy for understanding what DNS does, but the reality of how it works is more complex.

DNS resolver

When you enter a domain name into your browser’s URL bar, a DNS query is sent to a special server called a DNS resolver (also DNS recursor or just DNS server).

As its name suggests, the DNS resolver “resolves” the DNS query by retrieving the domain’s corresponding IP address and sending it back to your browser. Now that it knows the IP address of the website you want to visit, your browser can connect to it.

So far, so simple. But how does the DNS resolver retrieve the correct DNS address for a domain (a process complicated by the fact that new domains are created all the time, and IP addresses are often dynamically allocated to domains and therefore routinely change)?

How a domain is resolved using DNS

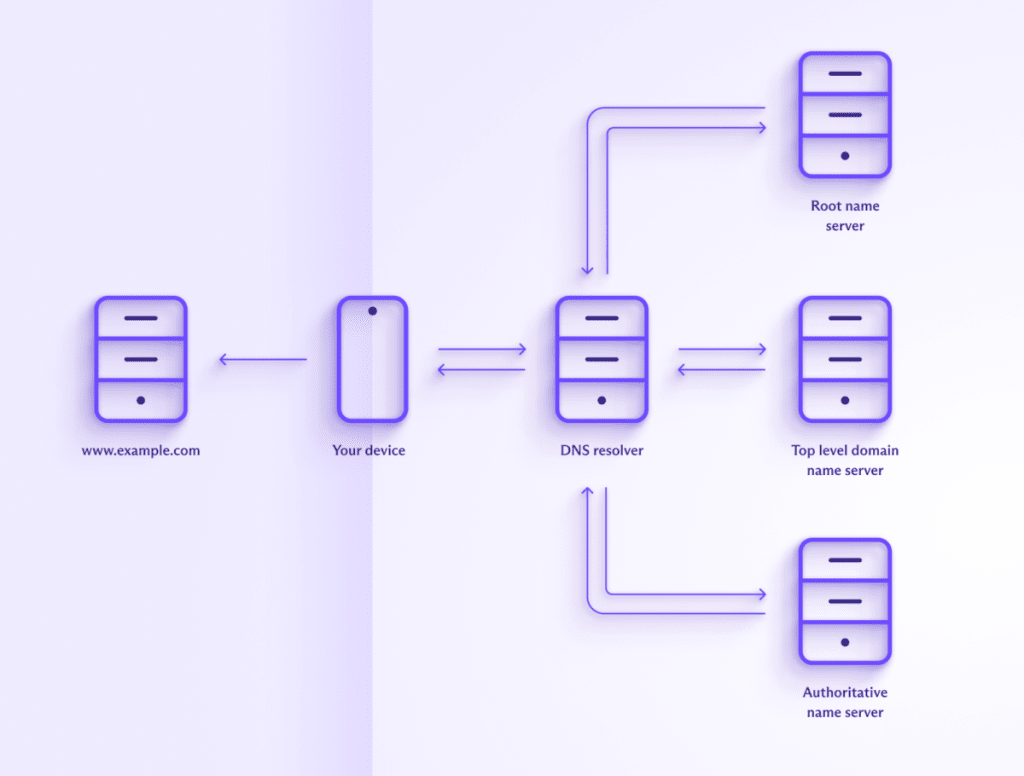

A DNS lookup for a top-level domain(새 창) (TLD) typically involves the following steps:

1. You type protonvpn.com into your browser’s URL bar. Your browser sends this query over the internet to a DNS resolver.

2. The DNS resolver sends a query to a DNS root name server. This is a server that stores information on TLDs (such as .com or .net, or country code TLDs such as .ch or .uk). For our query was (protonvpn.com), the DNS root name server would point to the DNS resolver for “.com” TLDs.

3. Armed with this information, the DNS resolver will now query the .com TLD name server, which maintains a list of all .com domains. The TLD name server responds with the IP address of the domain’s authoritative name server.

4. The DNS resolver can now query the domain’s authoritative nameserver. This is typically run by a domain name registrar(새 창) — a business that leases and manages domain names (such as GoDaddy or Namecheap). The authoritative nameserver is the final source of truth about the domain and can return its IP address to the DNS resolver (in our case, this will be 185.159.159.140).

5. The DNS resolver sends the correct IP address to your browser, which can now connect to 185.159.159.140.

In reality, the situation is a bit more complicated. For example, many domains are associated with multiple IP addresses (including both IPv4 and IPv6 addresses), and there will be additional steps if you visit a subdomain (such as blog.protonvpn.com).

Information is also routinely cached (stored locally) at all stages of the process — by your browser, by the DNS resolver, and by the various name servers. If the required information is found in a cache, then a request is not sent, which results in some steps being missed.

However, in essence, this is how DNS works for a fairly standard visit to a website.

DNS, censorship, and government surveillance

By default, your browser sends your DNS queries to a DNS resolver run by your internet service provider (ISP). Your ISP can use various methods to see what you do on the internet, but by far the easiest (and cheapest) way is to simply monitor your DNS queries.

Most government mass spying programs rely on requiring ISPs to keep logs of their customers’ browsing histories. And, because it is easy and cheap, most ISPs meet these legal obligations by only keeping DNS logs.

Similarly, when governments wish to censor internet content on social, religious, political, or “moral” grounds, they ask domestic ISPs to enforce these blocks. And the easiest way to do this is to block DNS queries to specified websites and apps.

Third-party DNS services

One way to avoid at least some of this censorship and surveillance is to use a third-party DNS resolver, such as Cloudflare 1.1.1.1 or OpenNIC.

Some of these services may have good privacy policies, but unless connections to the DNS resolver servers are encrypted using DNS over TLS (DoT) or DNS over HTTPS (DoH), your ISP can see the requests in plaintext should it choose to look.

Encrypting DNS queries makes it harder (and therefore more expensive) for an ISP to monitor your browsing history, but it can still fairly easily trace which websites and apps you connect to if it wishes to.

DNS and VPNs

When using a VPN (such as Proton VPN), your connection to the VPN server is encrypted. With some effort, your ISP can see that you’ve connected to an IP address belonging to the VPN server, but that’s it.

DNS queries are sent through the VPN tunnel and resolved by the VPN provider, which may run its own DNS resolver or use a third-party VPN resolver. This has no privacy implications since the DNS queries appear to come from the VPN server, not the VPN user.

It’s worth noting that there’s no need for encrypted DNS when using a VPN, as all DNS queries are sent through the encrypted VPN tunnel anyway.

It’s also not recommended to use a third-party DNS resolver together with a VPN. Configuring your system in this way may cause your DNS queries to be sent outside the VPN tunnel to the third-party DNS resolver.

NetShield Ad-blocker

Proton VPN offers NetShield Ad-blocker in all our apps. This is a DNS filtering feature that blocks DNS queries to domains known to belong to advertising companies, online trackers, and malware. It (and other similar DNS filtering services) works at the DNS resolver level by simply failing to resolve DNS queries to blocklisted domains.

Learn more about NetShield Ad-blocker

Technically, this constitutes a DNS leak (see below). This may not be a huge issue if the DNS query is encrypted and you trust the DNS resolver, but it introduces an unnecessary third party (and therefore potential point of weakness) into the equation.

DNS leaks

When using a VPN, all DNS queries should get sent through the VPN tunnel to be resolved by the VPN provider. If, for any reason, the DNS query is sent outside the VPN tunnel to a third-party DNS resolver, a DNS leak has occurred. Failure to properly route IPv6 DNS requests through the VPN tunnel is a common cause of DNS leaks.

Since this third party would likely be your ISP, DNS leaks are a serious privacy concern. Needless to say, all Proton VPN apps have strong built-in DNS leak protection.

Common DNS record types

Here are some of the key DNS record types that can be looked up:

- A (Address) Record: Maps a domain name to an IPv4 address. Example: example.com → 192.0.2.1

- AAAA (Quad A) Record: Maps a domain name to an IPv6 address. Example: example.com → 2001:0db8:85a3:0000:0000:8a2e:0370:7334

- CNAME (Canonical Name) Record: Maps a domain name to another domain name, effectively aliasing one name to another. Example: www.example.com → example.com

- MX (Mail Exchange) Record: Specifies the mail servers responsible for receiving email on behalf of a domain. Example: example.com → mail.example.com (priority 10 — the priority number indicates preference, with lower-priority requests preferred).

- PTR (Pointer) Record: Maps an IP address to a domain name, used primarily for reverse DNS lookups. Example: 192.0.2.1 → example.com

- NS (Name Server) Record: Specifies the authoritative name servers for a domain. Example: example.com → ns1.example.com, ns2.example.com

- SOA (Start of Authority) Record: Provides important information about the domain, including the primary name server, email of the domain administrator, domain serial number (which helps manage and synchronize DNS data across multiple DNS servers), and refresh retry, and expire timers (Example: example.com → ns1.example.com, admin.example.com, 2024041501)

- TXT (Text) Record: Holds arbitrary text data, often used for email validation (like SPF or DKIM) and other verification purposes. Example: example.com → “v=spf1 include:example.com ~all”

- SRV (Service) Record: Specifies the location of servers for specific services, such as the SIP(새 창) internet telephony protocol, the XMPP(새 창) messaging protocol, etc. Example: _sip._tcp.example.com → 0 5 5060 sipserver.example.com

- CAA (Certification Authority Authorization) Record: Specifies which certificate authorities (CAs) are allowed to issue certificates for a domain. Example: example.com → 0 issue “letsencrypt.org”

- NAPTR (Naming Authority Pointer) Record: Used for URL resolution and defining rewrite rules for various services like VoIP. Example: example.com → 100 50 “s” “SIP+D2U” “” _sip._udp.example.com

- DNSKEY: Contains the public signing key used in DNSSEC (suite of specifications designed to add an extra layer of security to DNS).

- . Example: example.com → 256 3 13 …

- DS (Delegation Signer) Record: Holds the hash of a DNSKEY record to secure delegations in DNSSEC. Example: example.com → 12345 13 2 …

- SPF (Sender Policy Framework) Record: Used to define which IP addresses are authorized to send email on behalf of a domain. Example: example.com → “v=spf1 ip4:192.0.2.0/24 -all”

DNS lookup commands

DNS commands are used to query, test, and troubleshoot DNS servers and records. These commands are essential for network administrators to ensure that DNS services are working correctly, as DNS is crucial for the resolution of domain names to IP addresses.

Below are some commonly used DNS commands. You can run these commands in a terminal window (Linux), Terminal (macOS), Command Prompt (cmd) or PowerShell (Windows), or even a terminal emulator app on your mobile device. Not all these commands may be available “out-of-the-box” on your platform, but in almost all cases they’re easy to install.

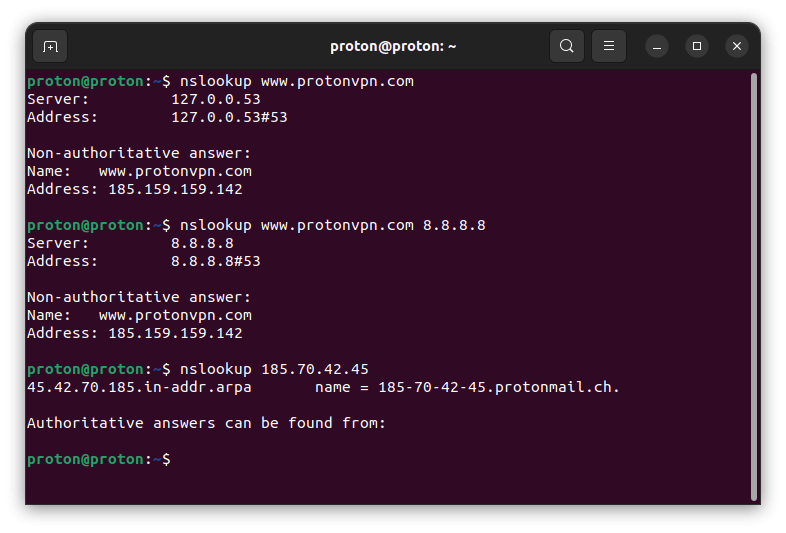

nslookup

The nslookup command is a tool for querying the DNS to obtain domain name or IP address mapping. You can also specify a particular DNS server to use and perform a reverse DNS lookup.

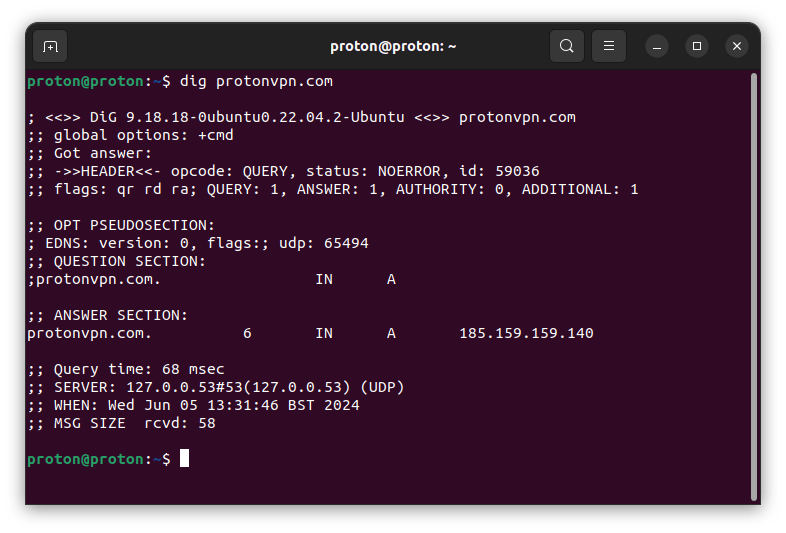

dig

The dig (Domain Information Groper) command is a more powerful and flexible DNS IP lookup tool than nslookup. Network administrators often prefer it for its detailed output and advanced options.

With dig, you can also query a specific DNS record type, query a specific DNS server, and perform a reverse DNS lookup.

host

The host command is another tool for performing DNS lookups. It’s simpler than dig but provides sufficient information for basic tasks, including querying a specific DNS server and performing reverse DNS lookups.

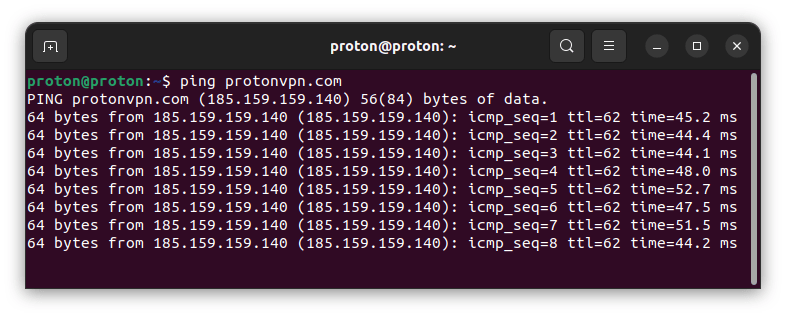

ping

The ping command is primarily used to check a host’s reachability on an IP network, but it also performs DNS resolution as part of its operation.

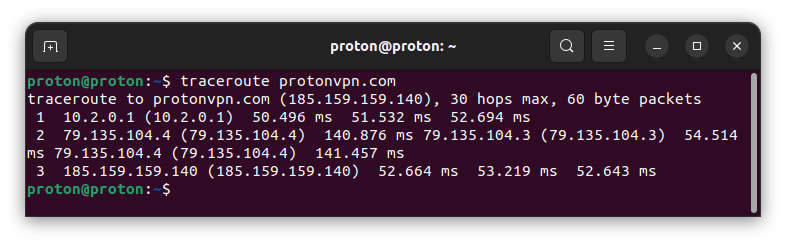

traceroute / tracert

The traceroute (on Linux and macOS) and tracert (on Windows) commands are used to trace a packet’s path, from its source to its destination. It resolves the domain name to an IP address and shows each hop on the way to the destination.

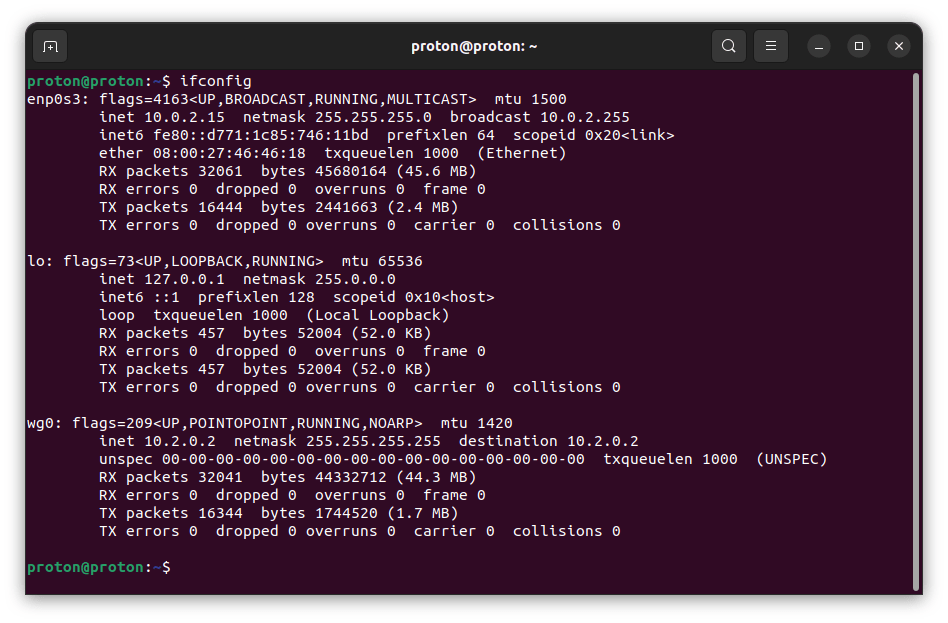

ipconfig / ifconfig

The ifconfig (on Linux and macOS) and ipconfig (on Windows) commands can be used to display network configuration, including the DNS servers that the system is using. When used on its own, it displays only active interfaces. To see all interfaces on Windows, use ipconfig /all.

DNS lookup tools

In addition to command-line tools such as those discussed above, there are many online DNS lookup tools that provide a graphic user interface (GUI) way to query DNS. A good example is our free secure IP scanner, which allows you to perform regular DNS lookups, MX lookups, NS lookups, CNAME lookups, and TXT lookups.

It can also perform reverse DNS lookups (IP lookup).

Final thoughts

At heart, DNS is just a complicated, automated phone book. It makes the internet usable for humans, but it can be (and is) abused by governments to spy on their citizens and censor what they see. The best way to bypass these abuses of DNS is to use a VPN service such as Proton VPN.

A VPN service securely resolves your DNS queries instead of your ISP, and most reputable VPN services make it their business to protect your privacy.

Of course, a VPN also offers many other benefits, such as hiding your real IP address from websites you visit, providing enhanced protection against IPS’s being able to monitor or censor your internet activity, being able to stream your favorite content when you’re traveling, and more.